What is on-chain cryptocurrency governance? Is it plutocratic?

This post is a response to a number of posts from prominent blockchain personalities about how on-chain governance based on coin-holder votes is inherently plutocratic and bad.

Vlad Zamfir— Against on-chain governance

Vitalik Buterin — Notes on Blockchain Governance

Vitalik Buterin — Governance, Part 2: Plutocracy Is Still Bad

Haseeb Qureshi — Blockchains should not be democracies

Dean Eigenmann — Against community governance

I find the use of the term plutocracy in this context to be inaccurate and alarmist. Blockchains are not societies, they provide a set of services, and do so in competition with other blockchains to which users can switch. Formal on-chain governance does not preclude a conventional hard fork.

Voting on changes to consensus rules is an interesting way to decentralize decision-making about the direction of a project. Awarding votes on the basis of Stake is, for now at least, the only viable prospect for making this approach work.

Blockchains don’t know how many individual users they have, but they know how many coins those users hold. People who hold coins, and who put them at stake, are invested in the project and have an incentive to try and make decisions which benefit it.

I am particularly interested in projects that aim to establish Decentralized Autonomous Organizations/Companies/Entities. Running a blockchain development project seems like the perfect fit for a DAO/C/E, with the blockchain itself serving as the source of funding and object of the work, with mechanisms for setting a purpose and strategic course, and deploying available resources to achieving that end.

Terminology and approach

On-chain governance is not a well-defined term, but it indicates that changes to consensus rules are not made in the conventional way (nodes switch to a new software version). On-chain governance implies a formal system operating on-chain that determines if and when changes to the consensus rules are activated. Projects that embrace this approach (or plan to) show significant variation, these projects are not a homogeneous set.

Coin-holder voting is a method of assigning votes to participants based on the number of coins (the project’s native asset) they hold. This is a misrepresentation of how most of the projects that have formal vote-based governance actually work. Typically holding coins is not enough to entitle one to vote, users must take some action to stake their coins. For Decred, one must lock DCR to buy tickets to participate in governance (and so the more precise term is ticket-holder governance). For Dash, one must hold enough DASH then run a masternode to participate in governance (and so the more precise term is masternode governance).

Stakeholder governance is accurate in the Proof of Stake sense, in that holders who have staked their coins are the governors. I don’t think the term stakeholder governance is great for this piece because it is often used to imply a variety of types of stakeholder. In stake-based governance the wishes of different stakeholder groups are reflected through the unitary dimension of how much they have staked.

Stake-based governance actually seems like quite an accurate term so I’ll go with that as a catch-all for this article.

There is considerable variation in how blockchain projects are governed, and that extends to projects that (plan to) have on-chain governance. Criticisms of on-chain governance can only be properly addressed in the context of a specific implementation. Decred is the project that I know best, and the only one I know of that already has functioning on-chain governance and a project fund, so I’m using it as an example.

I will use Ethereum as an example of a project without on-chain governance, for contrast, because the most compelling criticisms of on-chain governance come from people associated with Ethereum.

Incidentally, Ethereum is also one of relatively few projects to have actually held a coin-holder vote as a way of making an important decision — whether to adopt a hard fork change to the consensus rules to nullify the DAO hack. This vote was ad-hoc and informal, a signal vote to determine how a parameter in the new version of Ethereum node software would be set (to fork or not to fork). Vitalik’s post has a nice overview of “tightly coupled” and “loosely coupled” votes, and sees a role for coin-holder voting as part of “multi-factorial consensus”

What is Plutocracy?

A plutocracy or plutarchy is a society that is ruled or controlled by people of great wealth or income. — Wikipedia, 17th May 2018

The key aspects of this definition are 1) what is being governed, and 2) who are the governors, but I think it’s also important to consider how the governors set the rules.

What is being governed?

Plutocracy refers to governance of a society. Blockchains are not societies, but it’s hard to define what the appropriate frame of reference is because blockchains are a new class of socio-technological entity. Relevant frames which spring to mind are States, Companies and Utilities.

For me, the closest match for this purpose is with companies.

There are parallels between the holders of a cryptocurrency and shareholders in a company. Both own a quantifiable stake in some enterprise, but what that stake represents differs markedly between companies and cryptocurrencies (and within the set of cryptocurrencies, which are heterogeneous in this regard).

Shares represent equity or a stake in a company. Shares (usually) have voting rights. Shareholders vote to make certain decisions, sometimes to appoint representatives and sometimes to make decisions directly. Shareholders are entitled to dividends from the company’s profits. Shares can be bought and sold, their price is determined in the market by perception of the company’s value.

A company involves a set of participants with different roles working together to provide some product or service. Blockchains and cryptocurrencies are most similar to service-providing companies. A set of actors work together in various roles (e.g. developers, miners, marketers) to offer a service: an immutable censorship-resistant public ledger or something along those lines.

Customers, or users, derive some benefit from this service. They also have considerable choice in selecting a specific provider for the blockchain-based service they want, and the cost of switching between providers is low. Blockchains compete to attract and retain users in the same way that companies do.

For me, plutocracy implies a degree of subjugation, that the rich use their control to exploit the poor. I don’t see how a cryptocurrency’s governance can be any more plutocratic than a company’s. I cannot easily imagine a scenario where stake-voting whales really marginalize ordinary users, and those ordinary users just stick around and take it.

Cryptocurrencies with on-chain governance are also still subject to “governance by hard fork”, in the same way as every other cryptocurrency. In the same way that Bitcoin was forked to start Bitcoin Cash and increase the block size limit, and Ethereum was forked to undo the DAO, a project with on-chain governance could be forked to modify or replace the formal governance processes.

On-chain governance has to compete with more traditional forms of blockchain governance. Externally, there are more established projects that have been using, and presumably refining, governance by rough consensus, or “the full nodes”, for years.

Internally, off-chain governance is also an ever-present alternative, in that a hard fork that removed or nullified the on-chain governance of a blockchain would effectively be reverting to this more conventional approach to blockchain governance. No governance, at the protocol level, is like a default setting that is always available. On-chain governance will have to continuously show that it is a better choice.

Whether it is good for a blockchain to behave like a company is debatable, but that’s not the best question to ask. The company is a formidable organizational form, and projects that emulate elements from this template may gain a competitive advantage in doing so. The ultimate winners in the blockchain space will not be determined by what we decide would be nice here and now in 2018.

Governance is an attribute which will affect a blockchain’s prospects for success. I find it useful to consider cryptocurrency governance through the lens of Fitness from evolutionary biology — whether it makes the organism better suited to its environment and better able to out-compete its rivals.

How does stake-based governance work?

There are two types of decision-making for which stake-based governance is being used right now:

- Deciding whether to adopt changes to the consensus rules of the network. This is primarily what on-chain governance refers to. Decred is the only project I know of that’s already doing this. There is a formally defined process for changing the consensus rules, it is defined within the protocol itself. That process involves 75% of voting tickets saying Yes to the change within a voting period of 8064 blocks (~4 weeks).

- Deciding how to spend a project fund. There are quite a few blockchains now that put some proportion of the block reward into a fund for developing the project. Most of these projects (and all of the ones I’m interested in) aspire to decentralizing control of how these funds are spent. Dash has been doing this with a fairly simple DAO setup, operated by the votes of MasterNodes, for almost three years now.

There are a growing number of projects which aim to put stakeholders in direct control of both of these aspects of governance. Decred is the example I have chosen because it’s the project I know best (I have written about both Decred’s governance generally and how Politeia is intended to function for governance of the project fund).

The notion that ticket-holder voting should drive decision-making to the greatest degree possible across all aspects of the project is a good short-cut to understanding Decred’s approach to governance.

Decred’s ambition is to establish a Decentralized Autonomous Entity (DAE) driven by ticket-holder votes. The DAE’s purpose is to deliver value to the project by deploying DCR from the project fund to pursue its aims. The aims of the project are written down, and will be further negotiated and clarified through ticket voting on Politeia proposals once that system is live.

The project mission is to develop technology for the public benefit, with a primary focus on cryptocurrency technology. — Decred Constitution, 7th June 2018

This makes the development of the Decred DAE an interesting subject for research. It has a clearly defined set of goals and mechanism for adapting and adding goals, against which its performance can be assessed. Participation in governance is open to anyone who can afford a ticket (or, tenth of a ticket), and all of the decisions are a matter of public record. A broad basis of participation, on-chain votes, and the need to provide decision-makers with accurate information should ensure a high degree of transparency.

How I learned to stop worrying and love the stake-based governance

Source — Still from Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1964)

[Decred ticket-holders] [vote], on the basis of [one vote per ticket], to decide [how the protocol will evolve] and [how the project’s fund should be spent].

In that short description there’s a population [Decred ticket-holders], a method of decision-making [voting directly on issues], a rule for determining how many votes each member gets [one vote per ticket], and some examples of what will be decided.

Governance of the Decred project fund involves a lot of the same decisions as governance of more conventional organizations.

- Setting a strategic course for the organization

- Adopting and amending policies

- Selecting projects and teams to fund

- Deciding when a project has met its milestones and earned payment

- Evaluating proposal outcomes and learning to approve better proposals

- Hiring employees

- Terminating employees

- Managing official project social media accounts

Understanding how the various components of that governance can be effectively decentralized is relevant for other contexts. Changing some of the variables in the sentence affects how transferable the knowledge is, but considering how little we know about how to construct a high-functioning Decentralized Autonomous Organization/Company/Entity, we can learn a lot by studying projects built around this kind of concept.

Who are the blockchain’s stakeholders?

Some useful labels and how they apply to Decred and Ethereum:

Founders: The people who started the project and either a) self-funded initial development, or b) raised funds for initial development through Initial Coin Offering or other pre-sale. Founders are usually 1) well regarded and influential in the community, and 2) significant holders.

Developers/workers: Founders obviously overlap with this group, but I’m using it to refer to people who aren’t significant holders or otherwise wealthy. This group represents people who would like to work on the project, but can only spend significant time on it if they are paid.

Full Nodes: People running servers that autonomously participate in maintaining the network, validating that blocks follow the consensus rules.

Holders: People who use the cryptocurrency as a Store of Value, they hold it because they believe it will increase in value relative to other assets.

Other Users: People who want to make use of the service the blockchain provides, but don’t care to hold any coins.

PoW Miners: People who run hardware that secures the network by demonstrating Proof of Work. I wrote an introduction to PoW miners from a governance perspective here. Miners expend resources to perform their work and are rewarded with coins. Miners have a form of power because they are the creators of new blocks and can determine the content of those blocks. Miners have this power in proportion to the hashpower of the hardware they can deploy.

PoS Voters: A sub-set of Holders who participate in staking. Voters stake coins to perform their work and are usually, but not always, rewarded for doing so. Ethereum doesn’t have a class of PoS participants yet, but plans to adopt a Proof of Stake method of creating new blocks. Decred’s PoS Voters run the show, or will do eventually if the project succeeds.

Who are the stake-based governors and what do they do?

In Decred’s case, PoS Voters are people who time-lock some of their DCR in exchange for tickets. This group performs the following roles:

- Voting (on-chain) to decide whether changes to the consensus rules should be adopted.

- Coming soon: Voting (off-chain) to decide how the project’s fund should be spent. This entails voting to set a course for the project’s development.

- Voting (on-chain) to approve block validity. Each Decred block calls 5 tickets, these tickets vote on whether the PoW Miner should receive their reward for the previous block.

The importance of the third point has recently been put in focus by the spate of hashpower attacks on alt-coins. Within Decred’s system, PoW Miners can do nothing without the cooperation of PoS Voters. Blocks cannot be mined in secret because they require active participation of the pseudo-randomly selected ticket-holders to be valid. PoS Voters can also actively vote to allow the block to be added to the chain but withhold the miner’s share of the block reward (without sacrificing their own).

By establishing a group of PoS Voters on-chain, it can be given roles in the running of the protocol, and dominance over other actors like PoW Miners. The need to compromise both PoW and PoS components makes it significantly more expensive to attack Decred than pure PoW cryptocurrencies.

As a group, PoS Voters overlap with most of the other groups of actors. Founders, Workers, Miners and Holders all receive or hold DCR, and can time-lock some of it for tickets.

Stake-governors vs. users

One of Vlad Zamfir’s concerns about on-chain governance is that the interests of holders and users may not be aligned, and that holders may act in ways which benefit themselves at the expense of users. In Ethereum’s case, this makes some sense, because ETH is in part a utility token used to pay for the execution of smart contracts on the Ethereum blockchain. There may be Ethereum users who do not care to hold any ETH but need to buy it to run smart contracts. These hypothetical non-holding users would prefer ETH to have a lower price, and this would be in conflict with the wishes of holders for price increases.

It can be assumed that holders who stake their coins for some time period have an incentive for the price to increase. This aspect of stake-governor incentive can be assumed to conflict with parties who wish to see a decreased valuation. To the extent that the blockchain’s users treat it as a store of value, their incentives are well aligned with stake-governors.

A more likely avenue for conflict between users and stake-governors would be if PoS governors benefited from higher transaction fees. Transaction fees will affect one’s capacity to use a blockchain’s services more than price. Decred avoids this conflict for now, as PoS Voters do not receive any share of transaction fees and therefore do not stand to benefit from higher transaction fees. In future, as the emission of new DCR tails off, this may become a point of conflict. If PoS Voters were to decide to award themselves a portion of the transaction fees to make up for declining block rewards, this would have to be carefully negotiated so as to avoid losing PoW Miners and non-staking users.

Alternatives to stake-based governance

Every blockchain has a mode of governance, but for many it is difficult to pin down exactly how that governance works because everything happens off-chain. I have looked into the governance of Bitcoin and Ethereum, but there are significant gaps in my understanding. Vlad Zamfir has apparently been writing something about Ethereum’s governance processes for a while, but by his own description they are:

…not very well documented, and it’s hard to understand them without actively participating in them…No one has full information about the structure of the processes involved.

With off-chain governance, changing the consensus rules of the protocol requires that all of the relevant actors adopt software which implements the new rules, at the same time. Some entity has to decide that a change is required and coordinate the upgrade. This entity typically makes some sort of judgment call about whether there is support for a rule change, within each of the groups of actors they deem important. This entity must also be able to deliver the software which will implement these new rules, or there will be nothing for users to adopt.

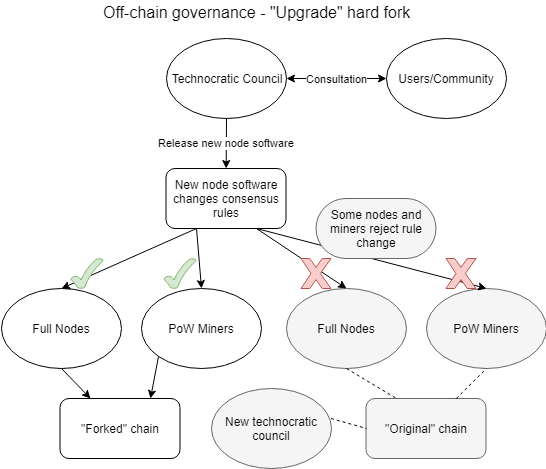

Dean Eigenmann uses the term “technocratic council” to refer to this type of entity, I think it’s quite a good one. For every cryptocurrency project one can identify some organisation or group that drives development, although the character of these groups varies considerably. There are various ways in which these technocratic councils can interact with other stakeholder groups. PoW Miners can typically signal their approval or rejection of a change on-chain in a way which is robust to manipulation. Full nodes can be “polled” by checking their software version, but this signal can be faked at little expense by spinning up many new full nodes (a form of sybil attack).

It seems likely that most technocratic councils also use social media signals (e.g. twitter, reddit, slack/discord/telegram) to gauge sentiment in the community beyond PoW Miners. Social media is vulnerable to manipulation, especially wherever algorithms that can be gamed by sock-puppet accounts are used prioritize messages (i.e. reddit votes, twitter trending). Social media channels are also susceptible to censorship by whoever controls them.

For people outside a technocratic council, participation in governance is limited to choosing which technocratic council to support (assuming there is more than one viable candidate, which is rare).

Assuming a given technocratic council is interested in listening to the wishes of users, it must be challenging to establish whether there is consensus for a rule change in this group. If a significant minority contingent (representing all the required actor types for the blockchain to function) adopts/rejects an incompatible change in the rules, a chain split occurs.

The greyed part doesn’t happen when the hard fork goes smoothly and is not contentious.

Proponents of on-chain governance would tend to see chain splits as sub-optimal, they divide communities and resources and weaken network effects. Where a method of on-chain governance is embedded in the foundation of a project, there is a built-in way of defining what the rules of the protocol are and how they can be changed. A hard fork and chain split can still occur, but the fork could only survive by modifying the governance system, and this would leave little doubt about which chain is the “original” one.

To me, chain splits don’t look attractive as a mechanism of governance long-term.

Blockchains cost money to develop and make some people rich

However a technocratic council functions internally, it makes decisions about the future of the project/chain and moves forward with implementing these in code. The requirement to manifest changes in code sets a barrier to entry for a viable technocratic council. The resources required by this group depend on the ambition of the project. Software developers with the appropriate skills to work on the code are a minimum requirement.

The people who are required to develop the project need an incentive to spend their time doing so. There is often a large overlap between a project’s Technocratic Council and its Founders. Founders are incentivized to work on the project if they have significant holdings. If the project has had any commercial success, Founders are probably independently wealthy at this stage and can afford to spend time on the project without compensation.

Most other potential contributors are going to want to be paid to work on the project. Neither organizations or individuals are likely to pay people to work on the project without some idea of the direction that work should go in, and motivation for funding work in that direction. If you are interested in where a particular project is going long-term I think it’s worthwhile considering “Who is paying people to work on this? and why?”

Resources, and the will to spend them on developing software which supports a blockchain, are minimum requirements for a technocratic council (and hence successful hard fork).

Many projects have an entity like a foundation or network of founders that is fairly well entrenched in controlling the direction the project takes. This entity has recognition from users, familiarity with the code-base, resources and motivation to drive the project forward. Ethereum has the Ethereum Foundation, which I believe has an endowment from the crowdsale. For most projects that held crowd-sales, the entity which ran (and profited from) that crowd-sale is (or is highly associated with) the project’s current technocratic council.

Weaknesses of stake-based governance

If the stake-governors of a project collectively make bad decisions through its governance processes, the project won’t do very well. Projects with systems and processes that can facilitate the expression of collective intelligence should do well, but we don’t yet know how difficult that will be to achieve in this context.

It is risky and hard to turn over control of consensus rules and/or a wallet full of cryptocurrency to the direct voting-operated control of a pseudonymous set of ticket-holders. Nobody knows how to construct a DAE that works well. Prior examples were/are either complex and broken (exploited, e.g. “The DAO”) or basic and in need of significant (centralized) hand-holding (e.g. Dash treasury DAO).

The reputation of the Decentralized Autonomous Entity through which stake-governor decisions are expressed and executed will also be important. The DAE is a counter-party for people who work on the project and are paid from the project fund. Any perception that the DAE has behaved in a dishonorable way towards contributors (e.g. refusing payment for work without reasonable grounds) would damage its capacity to recruit and negotiate terms with subsequent contributors — and cause broader damage to the project’s reputation.

There would be no easy way for a DAE to demonstrate a “change in management” which could speed recovery from damage to reputation.

The DAE also needs to avoid getting a reputation as a soft target for easy money. Dash’s formal governance of its treasury budget ends at a point where the voting outcome is calculated and DASH is distributed to the wallets associated with winning proposals. Dash’s system defaults to payment up-front and has historically not been well supported by off-chain mechanisms for following up on funded proposals and withholding funds until work is completed — although these support structures have been bolstered recently.

In Cardano’s recently published treasury paper, the story of how project funds are governed ends at the point where the winning proposals are selected and funded.

Any system that works on the basis of payment up front for successful proposals will be vulnerable to abuse. The alternatives are not easy to administer in a decentralized fashion.

The reputation of a DAE could also become a significant strength for projects with stake-based governance. The perception of a stable decision-making force would be a positive if the DAE is seen to behave fairly and make prudent decisions. This would inspire confidence in how the project responds to unforeseen challenges in the future. Governance models that give greater power to leaders or councils are more vulnerable to the departure or corruption of those leaders.

The distribution of coins for a project with stake-based governance is important, because of the strong relationship between holdings and decision-making power. If an individual or group controls enough stake to make unilateral decisions, the governance model becomes one of (obfuscated) dictatorship or oligarchy.

This has been factored into the genesis of Decred. A pre-mine of 1.68 million DCR (8% of the total supply) was split evenly between the developers who founded the project (who received 4%) and people who signed up for a free airdrop in January 2016 before the mainnet launched (2,972 of whom received a share of the other 4%, 282 DCR each). With just 30% of the block reward going to PoS Voters, even aggressive staking of DCR from the beginning would not have allowed one to maintain one’s relative share of circulating DCR. 60% of freshly minted DCR goes directly to PoW miners and the other 10% is available to be earned by people who work on the project.

For projects with stake-based governance, the greater the percentage of total supply which is distributed as a pre-mine or as part of an Initial Coin Offering, the greater influence this event and the character of its participants will exert on the project’s governance long-term.

Conclusions

Every cryptocurrency has some form of governance. Although we can make a broad distinction between on-chain and off-chain processes for changing consensus rules, there is considerable variation within each set.

Calling on-chain governance plutocratic is alarmist. On-chain governance shifts the default from “we can only change the consensus rules if everyone who matters agrees, or we chain split” to “we will change the protocol rules if 75% or more stake-governors support that” — it doesn’t prevent the former from happening.

Governance will play a role in the competition between blockchains for adoption. If some forms of governance are more effective in pursuing this end, they will proliferate.

In a recent article co-authored with Glen Weyl, Vitalik Buterin expresses an interest in quadratic voting and describes it as something which would be interesting to try for governing blockchains.

Now, and for the foreseeable future, blockchains have no concept of unique human identities. They do however know who controls which coins/tickets. If we want to experiment with formal governance that decentralizes decision-making through voting, awarding the votes on the basis of stake is the only viable option we have.

Assigning voting rights to people who put their coins at stake in some way has certain advantages:

- it is achievable now (without sacrificing pseudonymity)

- decision-makers represent the various stakeholder groups in a way which is sybil-resistant, and which gives greater say to those with more at stake

- broad-based participation requires transparency

We’ll find out in the next few years whether this approach works, or can be made to work, well. A high-functioning DAE at the heart of a successful cryptocurrency project could be significant, within and beyond the blockchain space.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to the following people from Decred’s Slack for great feedback on various drafts of this post, in chronological order: snr01, jy-p, Haon, bee. Also a general shout-out to the #governance channel, the insightful discussions there have influenced several points of this article.